Englishman Paul Rose has made exploration his lifelong career. The exploits of this dynamic professional diver, polar guide, mountaineer, expedition leader, yachtsman and instructor traverse Antarctica, Greenland, Everest and several oceans. Driven to discover and experience the Earth’s wonders at first hand, he is also motivated to share his adventures and observations in some of the planet’s most extreme places as an author, television broadcaster and public speaker.

In this interview with Julian Cribb for The Rolex Awards Journal, Paul Rose speaks of his hopes that the younger generation will take on traditional and new challenges, and explains why he has accepted an invitation from Rolex to be a member of the Young Laureates Programme’s inaugural jury, which will meet in March 2010.

Rolex Awards: In a career packed with adventure, exploration and discovery, what have been the high points for you?

Paul Rose: Unquestionably being Base Commander at Britain’s Rothera Research Station in the 1992 to 2002 was a career high point. To have the finest scientists and best support team in the world, what a challenge — and what an honour. You’re at the very end of the world’s longest supply chain, doing the world’s most challenging science. There were times when the job itself scared me half to death — but most of the time it was the most rewarding thing I’ve done.

In 1999, I was honoured with the Queens’ Polar Medal for developing Rothera Base from a field station with quite a lot of men and a large number of dogs into a proper scientific research station. I brought in the diving, and we developed proper laboratories. You don’t spend 10 years in the Antarctic without meeting your fair share of great challenges, some more life-giving and others more difficult — accidents, crashes and so on.

Rothera Research Station, Antarctica

What was the main thing you took away with you from that whole experience?

Working with the scientists down there I realized just how much I loved field science. The individual scientists would have a dream, an idea about a particular earth science process. Often it would be a long shot, involving years of gathering data and analysing it. In the Antarctic it is so difficult; most people would say: “It’s so cold” or “I’m so tired”, “It’s such hard work” or ”The travel is so complicated that we’re going to have to change our method.” The best field scientists don’t do that. They keep the quality going, after months in the field when everything seems to be against them, working in terrible conditions. That was where I developed my true love for field science.

What were the most memorable discoveries made during your time there?

The ozone hole. And our understanding of climate change. I remember receiving a message from headquarters in 2001 that something was happening at the northern end of the Antarctic; they could see it on the weather satellite. I got up there in an aircraft and, sure enough, there was a huge piece of the Larsen Ice Shelf floating off. I was seeing huge ice islands that I used to think of as mountains just breaking off from the mainland and drifting out to sea, right in front of me. This is climate change in action.

Also, I remember the day when my team managed to drill through the Ronne Ice Shelf. They’d spent years trying to get through it with a hot water drill. We were really excited because we’d overcome a great technical challenge. All you can see now is an upside-down barrel in this great white expanse. You lift the drum up and there are some instruments in there, measuring the flow of Antarctic bottom water that is one of the very important drivers of the world’s ocean currents. It was a hugely complicated, wonderful piece of world-leading research.

You did quite a lot of diving in Antarctic waters?

Diving is one of my great loves. To swim with one of the world’s best marine scientists, then come up [to the surface] and say: “Hey, what was that, we just saw?” and have them reply: “I don’t know.” I can barely describe the feeling. To be among the first people in the world to see whatever it was....

Paul Rose preparing to dive in Antarctica

What was it?

There were these long... they looked to me like gorgonians, big soft corals, but they weren’t really. Long things coming out the bottom. Purple. With green things like fluorescent tennis balls. Then there were these great worms on the bottom in the Antarctic. They were horrible things, about as fat as your finger and they lived in a swarm on the bottom. I never liked them very much, actually.

Then there were these sea spiders, which aren’t crabs, but genuine sea spiders. We had a lovely debate about them and how old they were. No one had any idea, but by careful research it turned out these things are very old indeed. And these huge sea lice, Glyptonotus. They are very odd. A kind of gigantism occurs down there. It is wonderful to do some dives, see these strange things, and then debate them over a cup of tea back at base.

There must have been some alarming moments too?

That’s right. Diving in the open water in the Antarctic is safe. Diving through the ice is also safe in a stable environment. But when the ice is moving, it’s very tricky. It may seem simple to plop down through the brash ice, but it only takes a bit of wind or current a long way away, and it can tighten the loose pack together and make it very difficult to get out. One day, we were diving to recover a lost piece of equipment. The water was quite murky and we swam in circles, searching, until our air was getting low. As we rose 30 metres off the bottom, we banged out heads. A large iceberg had come up on the current and run over our position.

It was a horrible moment. I could see our safety line going off at a sharp angle. So we followed it, very worried. We only had so much air. I was thinking: “Holy smoke, this is a huge iceberg that’s gone over us.” Under the berg were great fissures and shapes in the ice, things of great beauty — but the beauty was lost on me: I was keen to get out. We left the line and kept going, swimming around all the shapes. As we came up, I wondered if it was the surface — or a huge cave in the berg. We came up and were delighted to see it really was the surface. I remember looking at our boat crew — and they looked a lot worse than we did! The cup of tea back at base felt pretty good, I must say.

In our well-explored world, what opportunities remain for young adventurers today?

It’s all to go for. Many people have dived like I did, crossed the ice caps or reached the tops of many mountains. But I say to the coming generation: go and do it for yourself. You have to ground-truth it, experience it for yourself. We may understand a lot about, say, geology, but still the greatest experience is to go and stand on it, walk around it, feel it, climb underneath it.

I say to young explorers: get out there and see it for yourself, climb those peaks, run those rivers, cross those deserts, sail that ocean. I’m doing everything I can to encourage the next generation to get out there, feel it and do it, to touch it themselves. To write about it, talk about it, share it with others. This is one of the most powerful ways of understanding our planet. I have a huge amount of faith in our next generation.

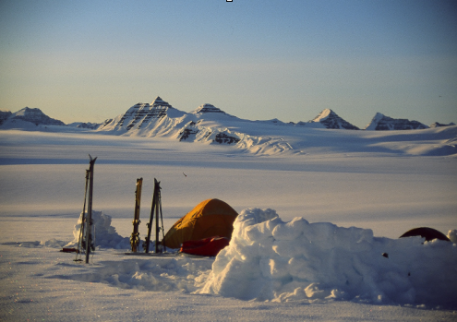

Paul's camp in the Watkins Mountains of Greenland

They have some great challenges ahead, haven’t they?

Yes. But what a time to be alive! We understand now that all six billion of us have, for the first time in history, become a force of nature. Our activities are affecting the planet’s systems — the oceans, rainforests, the temperature. We are having an effect on this beautiful planet. But as we become more aware of this, I believe we have — over the next 30 or 40 years — an opportunity to make a difference.

Being a part of the human race at this time is so energizing for me. We can learn about our world fast. We can share ideas fast. As these bright, young super-adaptors of the future come along, as they go out and see it for themselves, they are really going to make a difference.

The great leaders, educators and policy-makers of the future are growing up during a period of fabulous global discoveries. Yes, we’ve got some challenges, but I think we can make essential adaptations towards true global sustainability within the next 30 years.

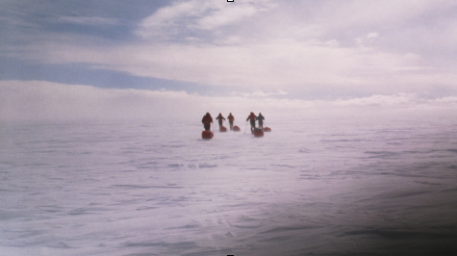

Paul Rose leading his team across the Greenland Icecap

In your exploration what did you see that impressed you about the scale of change we are causing?

My love is for the oceans, this vast, almost immeasurable space that makes up 99 per cent of the living space on the planet. We’ve only explored about 10 per cent of it.

When I am in the ocean I see huge rubbish islands, floating, massive amounts of plastic. In my early dives, I never saw such things. But, of late, I have seen a huge amount of waste. You can now find it on any coastline. I have never seen as much absolute rubbish, bottles, cans, debris, containers, all floating around in our seas. That’s a terrible legacy. It is really going to take some work to clean it up. In the North Pacific Gyre, this vast pile of rubbish about twice the size of Texas is going around in the ocean. When albatrosses die and you look inside them, they are full of lighters and bottle tops, bits of plastic rubbish.

I worked in the oil industry in the Middle East, and you can’t cross the desert without thinking: “Crikey. It doesn’t look like a desert any more. It looks like an oil field.” I just wonder if we can’t be very smart and use the oil and gas reserves we have now to develop new technologies — new wind, solar and other forms of power — and have an accelerated industrial revolution over the next 10 to 30 years. I’ve also seen how well we can clean things up.

What else have you observed?

Overfishing. When I dive the Sea of Cortez looking for hammerhead sharks, I don’t find one. That’s because we have taken millions and millions of sharks for their fins. On a massive, global scale, we are actually altering the food chain. Between 70 and 100 million sharks are caught every year, just for their fins. There just has to be a way of sharing that knowledge — that we don’t have to kill millions of sharks every year, that we are upsetting the balance in the world’s oceans. By sharing knowledge, I’m hoping people will make more sensible decisions for the future.

Paul Rose preparing to dive with Hammerhead Sharks

Is this the role of the young explorers of the future, to bring these things to our attention?

It’s absolutely a must. The young explorers of the future will have the natural energy, drive and curiosity to go out there, see for themselves, and then share it with others. Nowadays, they can go into the field and load their findings right onto the Internet — information that can be shared, analysed and used immediately. This means everybody can be a field scientist.

I encourage everyone, especially young explorers, to get out there and join us as citizen scientists. Science these days is something we can all go into.

What is your view of the Young Laureates Programme of the Rolex Awards?

It’s an absolutely fabulous opportunity. I’m a huge fan. With that cachet and the Award, you are really giving young explorers and innovators a fantastic level of support and recognition that they are doing the right thing. It carries the responsibility of doing even more work, being even more curious, continuing the legacy of past Laureates, and of feeding their findings back to all of us. It’s a truly wonderful thing.

What will you look for, as you judge this amazing array of talent and help choose the winners?

When I judge the Awards, I’ll be faced with a lot of very, very talented individuals and their ideas. I will look for people who are totally determined and focused on their project: that is what will keep the quality high. They will need to be absolutely tenacious, for the studies and journeys they will make. And also that these young explorers and original thinkers will be generous with their time and their findings. They will share their legacy — and it will spread globally.

Paul Rose was the expedition team leader and lead Presenter in the production of the recent eight-part BBC Oceans series involving scientific underwater expeditions at 50 locations worldwide to build a global picture of our seas. Oceans is available on DVD.

Reprinted from The Rolex Awards Journal No.26 February 2010